We notice the total range, and then we adapt our estimates” using our memory of previous sensory experiences, he said. “Our brain manages to very, very quickly scan the field. The findings confirm that “we don't have an absolute fixed scale of happiness and sadness in our brain” – and that a lot depends on context, the researcher explained. “They were perceived a little sadder” than in the first experiment, said Kornmeier.

In this test, the original was still described as happy, but participants' reading of the other images changed. Instead, “to our great astonishment, we found that Da Vinci's original was… perceived as happy” in 97 percent of cases.Ī second phase of the experiment involved the original Mona Lisa with eight “sadder” versions, with even more nuanced differences in the lip tilt. “Given the descriptions from art and art history, we thought that the original would be the most ambiguous,” Kornmeier said. In every showing, for which the pictures were randomly reshuffled, participants had to describe each of the nine images as happy or sad.

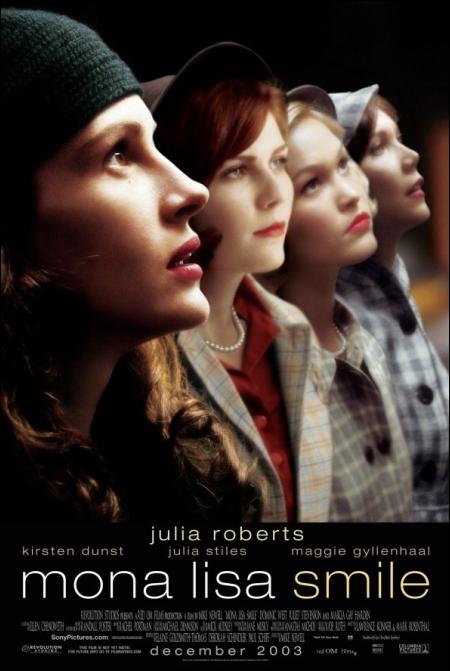

MONA LISA SMILE TRIAL

Using a black and white copy of the early 16th century masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci, a team manipulated the model's mouth corners slightly up and down to create eight altered images – four marginally but progressively “happier”, and four “sadder” Mona Lisas.Ī block of nine images were shown to 12 trial participants 30 times. The portrait appears to many to be smiling sweetly at first, only to adopt a mocking sneer or sad stare the longer you look. Known as La Gioconda in Italian, the Mona Lisa is often held up as a symbol of emotional enigma. Kornmeier and a team used what is arguably the most famous artwork in the world in a study of factors that influence how humans judge visual cues such as facial expressions.

“We really were astonished,” neuroscientist Juergen Kornmeier of the University of Freiburg in Germany, who co-authored the study, told AFP. In an unusual trial, close to 100 percent of people described her expression as unequivocally “happy”, researchers revealed on Friday.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)